As the world emerges from the Covid-19 pandemic, social isolation has been a much discussed topic. And while it comes as no surprise that periods of social isolation can have detrimental effects on mood — increasing the risk of developing anxiety, depression, and even PTSD — long-term isolation can also have a profound impact on the brain itself.

A multi-year study by Shannon Harding, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, and Aaron Van Dyke, PhD, associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry, uncovers differences in the way male and female rats respond to social isolation. Their study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Behavioral Neuroscience in 2024.

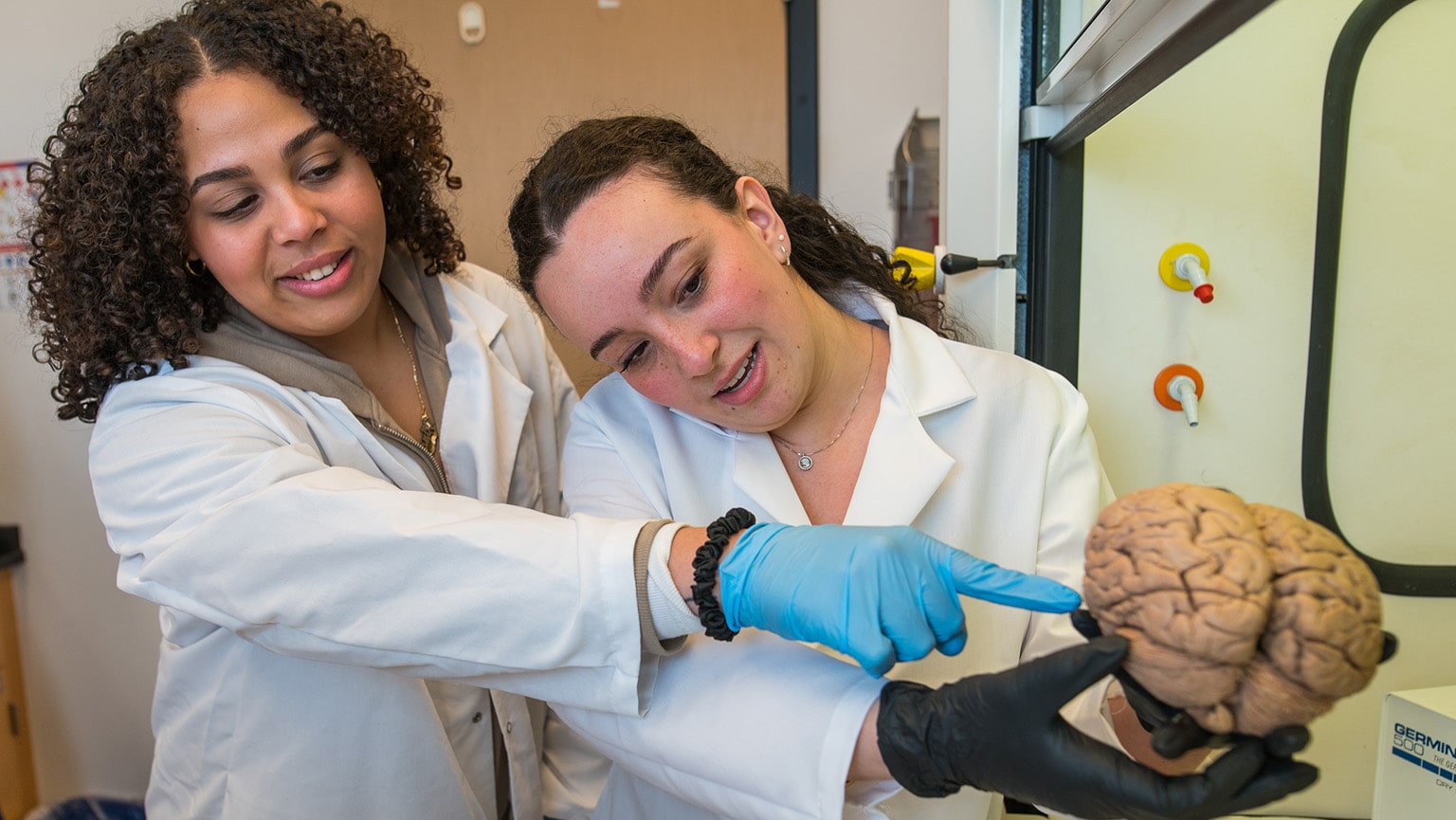

Dr. Harding and her students have been looking at the effects of social isolation through various lenses, such as gender differences and behaviors. They began by isolating a group of Long Evans rat pups in isolation for five weeks. The researchers then observed and tested these rats to measure changes in behavior, anxiety, and cognitive function, giving them tests to measure their performance against a group that was socialized normally.

“What we found is that males may be more sensitive to social isolation, especially when it comes to anxiety and cognition,” said Dr. Harding. “The female rats showed deficits in anxiety, but not in spatial memory.”

An essential part of any study is a literature review to find out what experiments have already been done, what the conclusions were, and what a new study could add. Research revealed studies showing that the semi-essential amino acid taurine – found in eggs, meat, fish, and some energy drinks—supports the healthy functioning of the heart, brain, and nervous system.

“It’s abundant in the body when you’re younger, and then dissipates with age,” said Jenna LaRochelle ’25, a neuroscience major who has worked with Dr. Harding for two years. “We hypothesized that supplementing the rats with taurine could be a potential treatment.”

Their findings? In general, the male rats responded well to taurine: A one-percent taurine solution in drinking water for five weeks resulted in the restoration of their spatial memory. Since female rats did not show a marked decrease in spatial memory, taurine treatment didn’t apply to them.

The results of the study, which demonstrate that social contact is vital for behavior and normal brain development even in lower-level organisms, are significant given the increased incidence of anxiety disorders in adolescents. While this study involved rats, it sheds light on how isolation during the formative years affects mental health.