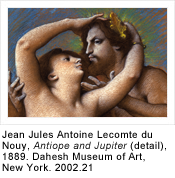

The Essential Line: Drawings from the Dahesh Museum of Art

The Bellarmine Museum

October 11, 2012 - January 18, 2013

This exhibition of works on loan from the Dahesh Museum of Art celebrates the act of drawing in the 19th century, when the creation of preliminary works on paper was the cornerstone of proper academic training and art-making. Embracing a broad range of subjects, the stunning pieces in this show are united by their creators' emphases on careful draftsmanship and extraordinary skills. Highlights include drawings by Thomas Couture (French, 1815-1879), Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822-1899), Frederic Lord Leighton (English, 1830-1896), Lawrence Alma-Tadema (British (born in the Netherlands), 1836-1912), and Alexandre Cabanel (French, 1823-1889).

The roots of the academic art tradition can be traced back to 1563, when the Accademia del Disegno was founded in Florence under the aegis of Cosimo I de' Medici (1519-1574). This institution, which consciously followed the written descriptions of the lost academies of ancient Greece and Rome, catalyzed the creation (under Pope Clement VIII Aldobrandini -69) of the Roman Accademia di San Luca in 1577 as well as the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, inaugurated in 1648 by France's Louis XIV (1638-1715). These canonical institutions in turn inspired a host of imitators during the 18th century, which witnessed a veritable mania for state-sanctioned academies. Indeed, by the close of the Age of Enlightenment, Europe boasted more than a hundred such bodies; a five-fold increase over the nineteen that existed in 1720. Despite their vast geographic spread (they stretched from St. Petersburg to London), these academies" like their venerable forebears in Florence, Rome and Paris" shared a steadfast commitment to disegno, a term referring to the hybridized mastery of both design and drawing that could be attained only through carefully studying and copying accepted exemplars. To ensure the centrality of disegno to artistic practice, rigid curricula were instituted in Europe's many academies. Neophytes would begin with the intensive study of individual physiognomic details before advancing to copying the Old Masters (generally through prints and engravings). Having mastered these fundamentals, students were permitted to make renderings of classical statues and plaster casts from antiquity and the Renaissance, after which they would proceed to drawing from life (a critical exercise that even seasoned academic artists would turn to throughout their careers). Only after successfully completing each of these steps would young painters launch into serious assays in oil; a progression that typically took between five to eight years to complete.

Drawing continued to serve as a critical tool in practioners' creative arsenals well into the 19th century, despite the incursion of significant new movements, including Romanticism, Realism and Impressionism. Its on-going relevance may be ascribed to the fact that such works served many different ends. Drawings were used not only as preparatory materials for highly finished paintings or prints but also as sketches in which artists either conceived new works or developed nascent ideas. They were tangible records of abstract thoughts, expressed in concrete visual terms, as well as the immortalization of new sources of inspiration (recalling that photography was only invented in the mid-19th century). Endlessly flexible, the act of drawing could be harnessed in the service of elevated classical themes as well as low-brow humor through caricatures or proto-cartoons, in addition to all genres in between. The results could be highly finished, stand-alone works or the loosest of sketches, intended for no eyes other than the artists' own. Whatever the case, the resulting images remain critical cultural and historical documents as well as compelling aesthetic objects, as The Essential Line: Drawings from the Dahesh Museum of Art confirms. These works not only reveal a wealth of incredible technical skill "hard won after years of strictly disciplined practice and training" but also remind us of the great range of styles and approaches that are possible under the misleadingly corseting label of "academic art."